In November 1923, the local newspapers were full of the story of Elijah Bundock, a minister of the Apostolic Church of Canada who was attacked on November 13th. The first report in The Daily Intelligencer read:

When he left the Apostolic Church, Stirling, last night after having conducted a service there, Rev. Bundock, who has been living in Stirling for two years, was seized by a group of strange men, was driven to Anderson’s Island… and there he is alleged to have been beaten, tarred and feathered. It is alleged that financial matters and misconduct on the part of Bundock was the cause of the treatment accorded him.

The Stirling News-Argus had a slightly different take on the night’s events:

Rev. Bundock, of the Apostolic Church, was tendered a warm, though not unexpected reception on Tuesday evening when several citizens of the town and vicinity…treated him to a drive in the country landing finally at Anderson’s Island, where they showed still further generosity by making a slight addition to his toilette in the way of tar and feathers. This demonstration of affection was accompanied by a very earnest request that he continue his journey, making tracks with his heels towards Stirling, or a still greater display of feeling would be manifested by all present…

Mr. Bundock has been in Stirling for a couple of years and claimed to be a faith healer. For various reasons he has not been popular with the people generally and the present trouble, which rose over some property question, served to bring to a head the feeling which has accumulated during the year.

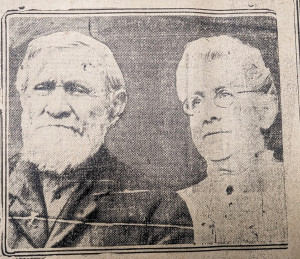

Elijah Bundock was a 50 year-old married Englishman and the father of five children. The family had arrived in Canada in 1909. At the time of the attack, Bundock was living with the Stewart family of Stirling.

According to the 1921 census, the Stewart household comprised Mary Elizabeth Jane Stewart, aged 66, her 74 year-old husband Hugh, their unmarried daughter, Tryphena, 38, and Elijah Bundock, their lodger, 48. The Stewarts had ten other children, who had all left home by this time.

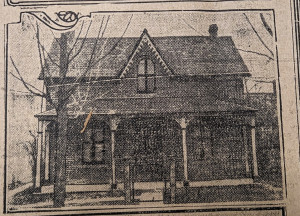

Hugh was described in the Daily Ontario as an invalid, and their property on Henry Street in Stirling was in his wife’s name.

According to the Daily Intelligencer, Bundock had been living with the aged couple and their daughter and had “made a financial agreement with the parents by which they deeded their farm over to him on condition that he keep them while they lived… Bundock apparently had not been keeping his share of the bargain as there were quarrels in the Stewart household and the old lady had left Friday last”

Bundock had arrived in Stirling in around 1920, and built a church there. The newspaper reported that his wife, Florence, and their youngest son, Hubert, lived elsewhere in the village (although they aren’t listed in the 1921 census).

But by 1923 Bundock’s congregation had dwindled to just seven people: and they were all members of the Stewart family.

It sounds as though people in Stirling had little sympathy for Elijah Bundock and they turned out in force on November 23rd for the Belleville trial of the six young attackers. The men in question were Roy Belshaw (22), Percy Chard (19), Reuben Chard (19), Norman Sine (25), William Tulloch (17) and Earl Wallace (22).

The Daily Ontario reported that:

The police court room was never more congested than it was when Magistrate Masson took the bench. Every seat had been taken half an hour before court opened and at ten o’clock aisles were jammed with spectators, the constables having to clear the passages leading to the prisoners’ dock

According to the Intelligencer’s editorial on November 24th, Magistrate Masson took a stern view of the Bundock affair.

His Worship was convinced not only that the laws of the country had been contravened but that a menacing spirit of Bolshevism had been exhibited.

“I will check this Bolshevism and mob rule,” Masson stated as he handed the young men six-month suspended sentences and jointly fined them $100 to compensate Reverend Bundock for the ruin of his suit.

And as far as the newspapers were concerned, that was the end of the affair, but it is worth digging a little deeper to find out what became of the main characters.

At the time of the 1931 census Elijah Bundock was living in the tiny village of Nolalu, to the west of Fort William, or Thunder Bay, as we know it today. His household consisted of two people: Elijah Bundock, 58, and Tryphena Stewart, 48, who is listed as his sister.

Florence Bundock, Elijah’s wife, was living with two of her daughters on Yonge Street in Toronto. Her two surviving sons were also nearby, on Eglinton Avenue and Mount Pleasant road.

Elijah Bundock died on May 9th, 1949, in Nolalu at the age of 75. His death certificate notes that he was separated from his wife, Florence, and his death was registered by Miss T. Stewart. This time her relationship to Bundock was given as “Housekeeper”.

Elijah Bundock was buried in the Mountain View cemetery in Fort William. It’s not clear what became of Tryphena after his death.